Photos of an eclipsed Moon are distinctive and can be very rewarding to capture. The next opportunity to capture one is the night of March 13th-14th, 2025. But shooting an eclipse, even a lunar eclipse, can be a little intimidating. Follow along with this tutorial and learn to stop worrying and to love photographing the lunar eclipse.

Viewers in much of the Western Hemisphere, Oceania, Western Europe and Africa, and the eastern parts of Australia will be treated to a Total Lunar Eclipse on 13-14 March 2025. While not an exceedingly rare occurrence, a total lunar eclipse is still special enough for you to enjoy it. If you missed this one, you must wait until 3 March 2026 for your next chance to see one from the western hemisphere, and only on the west of edge of North America. (The next total lunar eclipse actually on 7-8 September 2025, but you’ll have to be in Eastern Asia, Australia, and eastern Africa.)

Considerations for Photographing a Lunar Eclipse

Even with experience photographing the Moon under regular conditions, a total lunar eclipse poses several issues:

- The contrast range during partial phases is large and will push your camera sensor to its limit.

- The Moon can be as much as 19 stops dimmer during totality than when full, meaning long shutter times.

- The motion of the Moon begs for tracking due to the long exposures needed during totality.

Cover Photo: A Total Lunar Eclipse of the Moon. Photographed on 9 October 2014 with a 1260mm lens. Photo Credit: ©2018 Kirk D. Keyes

As an Amazon Associate, PhotographTheMoon.com earns from qualifying purchases.

Camera Equipment

You don’t need a lot of camera gear to photograph a lunar eclipse. The most important things are a camera with manual settings and a tripod. A point-and-shoot camera with a “super-telephoto” lens will work. You can also successfully use an iPhone or other cell phone camera if it has exposure controls.

Lens choice depends on the image type, so anything you want, from a wide-angle to telephoto, can be used. The classic photo of an eclipsed Moon is taken with a long telephoto to get a close-up view.

An intervalometer or remote shutter release is also helpful but not required. If you have one, a star tracker can be very helpful for following the Moon as it moves across the sky.

Quick Section Navigation

Follow the links below to jump to other parts of this article.

- Learn About this Eclipse

- What is a Lunar Eclipses

- Planning Your Shoot

- Lens Choice

- Camera Gear to Photograph the Total Lunar Eclipse

- Setting Up

- Lunar Eclipse Exposure Settings

An Exceptional Eclipse

The 13-14 March 2025 eclipse will be noteworthy for several reasons. First, the Moon was well within the darkest part of the Earth’s shadow. Second, for observers in northern latitudes, it will be high in the night sky. It will take a little more work for the photographer to incorporate totality into a landscape photo than last January’s lunar eclipse.

Seeing a total lunar eclipse can be a very inspiring experience. Take a child you know out and share it. I think the first lunar eclipse I saw was a total eclipse in May 1975. I was 12 at the time, and it inspired me to learn more about the night sky and how to photograph it. Heck, take an adult you know!

When and Where

This total lunar eclipse occurs from the night of March 13th to the morning of March 14th, 2025. The entire eclipse will be visible to North and much of South America. Partial phases from Europe and western Africa can be seen on the evening of March 13th. The eclipse will occur on the morning of March 14th, with a moonrise in the western Pacific.

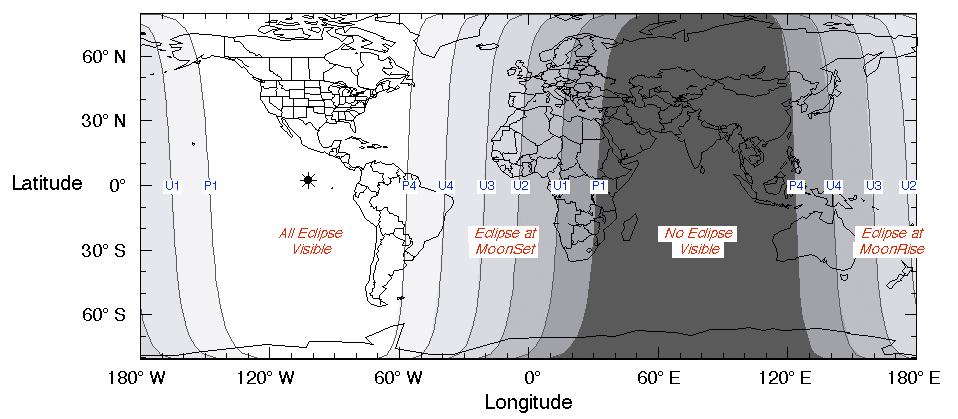

Map of Eclipse Visibility by Location.

This map shows where the Moon will rise or set during each eclipse stage. See the “Stages of a Lunar Eclipse” section to find out what the line designations mean. Graphics courtesy of F. Espenak, NASA.

What is a Lunar Eclipse?

As the Moon passes on the opposite side of the Earth from the Sun, it sometimes passes through the Earth’s shadow. It usually misses, but sometimes, it does contact the shadow, usually two or more times each year.

Since the Sun is larger than the Earth, the Earth’s shadow consists of a brighter outer ring and a darker inner ring. The outer ring is called the “penumbra” and the inner ring the “umbra”. It’s easy to remember what these words mean by looking at the Latin roots – first, “umbra” means “shadow”. Penumbra uses the word “paene” which means “nearly, almost”, so it means “almost shadow”. Just like penultimate, it is not quite as important as ultimate.

The sun is entirely obscured when looking towards the sun from inside the umbra. When viewing from inside the penumbra, one edge of the sun is still visible. So, the penumbra is not as dark as the umbra.

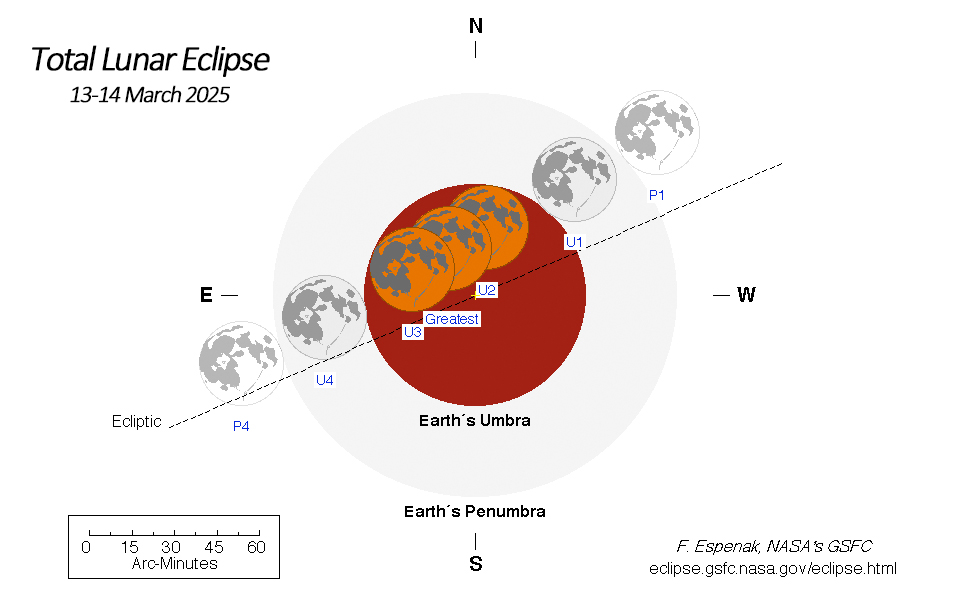

The path of the Moon as it travels through the penumbra and umbra shadows. In a Penumbral Lunar Eclipse, the Moon will only enter the penumbra but never cross into the umbra. With a Partial Lunar Eclipse, the moon travels north or south of the umbra and enters it, but never makes it in. And with a total lunar eclipse, the umbra completely covers the Moon.

Graphics courtesy of F. Espenak, NASA.

Types of Lunar Eclipses

There are three types of lunar eclipses:

- Penumbral Lunar Eclipse – When the Moon passes into the Earth’s penumbral shadow but not into the umbra. This type of eclipse is sometimes not very noticeable and is often hard to see.

- Partial Lunar Eclipse – When the Moon passes into but not entirely into the Earth’s umbral shadow. This type is easy to see, but it does not cover the entire Moon.

- Total Lunar Eclipse – When the Moon travels completely into the umbra and no direct sunlight falls on the Moon’s surface. This produces a much darker eclipse than a Partial or Penumbral Eclipse.

Stages of a Lunar Eclipse

Astronomers have notations for each stage to simplify discussing lunar eclipses. A lunar eclipse has six points when the Moon “contacts” a different part of the Earth’s shadow.

- P1 – Penumbral Eclipse Begins when the Moon contacts the Earth’s penumbra.

- U1 – Partial Eclipse Begins when the Moon contacts the Earth’s umbra.

- U2 – Total Eclipse Begins when the Moon fully enters the Earth’s umbra.

- Greatest Eclipse when the Moon is at the center of its path through the umbra.

- U3 – Total Eclipse Ends when the Moon begins to leave the Earth’s umbra.

- U4 – Partial Eclipse Ends when the Moon begins to leave the penumbra.

- P4 – Penumbral Eclipse Ends when the Moon loses contact with the Earth’s penumbra.

The Earth’s penumbra will first appear on the eastern edge of the Moon. It will be seen as a faint darkening on the eastern side of the Moon and continue moving across the lunar surface towards the western edge. Since the penumbra is only slightly darker than the direct sunlight illuminating the rest of the Moon, it may take about 15 to 25 minutes after the eclipse begins (P1) before the penumbra becomes noticeable. The penumbra should be obvious by the time it has covered about one half of the Moon.

After a while, a darker shadow, the umbra, will also appear to move across. The umbral shadow is easily seen. Even after the umbra covers the entire Moon during totality, one edge of the Moon will be brighter than the rest as the Moon rarely travels precisely through the center of the umbra. This brighter edge can appear on the northern or southern margin of the Moon’s surface. During the 13-14 March 2025 eclipse, it will be along the north edge of the Moon.

Blood Moons

The type, length, and depth of a total lunar eclipse depend on how perfectly the Sun, Earth, and Moon are aligned. The closer they are aligned, the more deeply the Moon moves into the Earth’s shadow. This affects how dark the Moon appears.

Graphic credit: Eggishorn (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Blood_Moon_Corrected_Labels.png) https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/legalcode

The color of the normally monochrome Moon during an eclipse is affected not only by how deeply it passes into the umbra but also by the atmosphere of the Earth. Even though the umbra doesn’t contain any direct sunlight in it, it does have sunlight that has been refracted by the Earth’s atmosphere. Just as the Sun’s light is refracted at sunrise or sunset on Earth, the color of this refracted light is redder than sunlight. This reddish light turns the moon a coppery or reddish color.

The red color can become more intense from the scattering of blue light in the Earth’s atmosphere. When the atmosphere contains more water, aerosols, or particulates like dust than expected, the blue light will filter and scatter out of the atmosphere. A large volcanic eruption can put so much particulate into the Earth’s atmosphere that it will darken eclipses for several years. When this happens, the moon will have a deep red color, sometimes called a “Blood Moon”.

Not Always a “Blood Moon”

Don’t be misled by the popular press into calling every total lunar eclipse a “blood moon”. Eclipses can have a wide range of shades. The alignment of the Earth, Sun, and Moon greatly affects this. Brighter eclipses can have a distinctly blueish tinge to the rim of the Moon. Sometimes this brighter edge can make viewers question whether a total eclipse was truly total.

The Danjon Scale (devised in 1921 by French astronomer André-Louis Danjon) measures the appearance and luminosity of the Moon during a lunar eclipse. The scale is denoted by the letter “L” and has values from 0 to 4, with L0 representing the darkest and L4 the brightest.

Danjon Scale

![Danjon Scale

Credit: Thóumas [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], from Wikimedia Commons](https://photographthemoon.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/image.png)

Danjon Scale

Credit: Thóumas [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], from Wikimedia Commons

The colors of the Danjon Scale can be divided as follows:

- L0 = Very Dark Eclipse. The Moon is almost invisible, especially at mid-totality.

- L1 = Dark Eclipse. Brownish or grey in coloration. Details on the lunar surface are difficult to distinguish.

- L2 = Deep Red or Rust-Colored Eclipse. The central shadow is very dark while the outer edge of the umbral shadow is still relatively bright.

- L3 = Brick-Red Eclipse. The umbral shadow on the rim is bright or yellow.

- L4 = Very Bright Copper Red or Orange Eclipse. The umbral shadow has a very bright or bluish rim.

Determining the “L” value for an eclipse is best done with the naked eye, small binoculars, or a small telescope during mid-totality. Also, compare its appearance with just before and just after mid-totality. Amateur observers are encouraged to make Danjon Scale observation reports to Sky and Telescope and to Dr. Richard Keen (richard.keen@colorado.edu).

For this January’s eclipse, the Moon will pass north of the umbral center, so the northern edge of the Moon will probably be brighter than the rest. The lower part will be noticeably dimmer and probably redder. That said, many variables affect the color and darkness of the Moon and it can vary greatly.

Lunar Eclipse Timing

Lunar eclipses typically last a few hours, with the maximum totality lasting up to 107 minutes. They may be seen from anywhere the Moon is above the horizon. They can even be seen before or after sunrise or sunset. Unlike solar eclipses, no special viewing precautions are needed to look at a lunar eclipse, as it is dimmer than a full Moon.

For observers in the contiguous USA and Canada, the January 2019 eclipse will start after sunset with totality beginning before midnight. Be prepared for a late night on the eastern margin of the continent if you want to see the eclipse in its entirety, as it ends well after midnight there. Those on the west coast will have an early evening with the eclipse wrapping up shortly before midnight. Remember to dress warmly!

Phase Durations

The entire eclipse (P1 to P4) will last 6 hours and 3 minutes, the umbral phase (U1 to U4) will last 3 hours and 38 minutes, and the totality phase (U2 – U3) will last 65 minutes. Once the totality phase ends, most people call the evening good, with only the most die-hard of eclipse watchers remaining until the P4 stage.

The Moon will be high in the sky for viewers in the USA. At mid-totality, the Moon will be nearly 57° above the horizon from Miami. That’s nearly straight overhead. It’s lower for viewers further north and further west. In Chicago, the Moon will be 48° up at mid-totality, a mere 50° for Salt Lake City, and Seattle gets off with 41°. If you’re lucky enough to be at the Mauna Kea Observatories in Hawaii, you’ll be treated to a Moon only 35° above the horizon at the point of the greatest eclipse!

13-14 March 2025 – Eclipse Stages by Time Zone

Total Lunar Eclipse Timetable 2025-03-14| Time Zone | PDT | MDT | CDT | EDT | UTC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Difference from UTC | -7 hr | -6 hr | -5 hr | -4 hr | ||

| Date: | March 13 - Thursday | March 13 | March 13 | March 13 | 14 Mar 2025 | |

| Penumbral Eclipse starts | P1 | 8:57:28 pm | 9:57:28 pm | 10:57:28 pm | 11:57:28 pm | 03:57:28 UT |

| Partial (Umbral) Eclipse starts | U1 | 10:09:40 pm | 11:09:40 pm | Mar 14 at 12:09:40 am | Mar 14 at 1:09:40 am | 05:09:40 UT |

| Full Eclipse starts | U2 | 11:26:06 pm | Mar 14 at 12:26:06 am | 1:26:06 am | 2:26:06 am | 06:26:06 UT |

| Maximum Eclipse | MAX | 11:58:43 pm | 12:58:43 am | 1:58:43 am | 2:58:43 am | 06:58:43 UT |

| Full Eclipse ends | U3 | Mar 14 at 12:31:26 am | 1:31:26 am | 2:31:26 am | 3:31:26 am | 07:31:26 UT |

| Umbral Eclipse ends | U4 | 1:47:52 am | 2:47:52 am | 3:47:52 am | 4:47:52 am | 08:47:52 UT |

| Penumbral Eclipse ends | P4 | 3:00:09 am | 4:00:09 am | 5:00:09 am | 3:00:09 am | 10:00:09 UT |

Planning Your Shoot

Planning is an integral part of photographing a Lunar Eclipse. Even though a total lunar eclipse takes hours to complete, you don’t want to waste your time running around when you could be taking photos.

Practice, Practice, Practice

Get out a few days or even a week before the eclipse and test your camera set up. The Moon’s brightness a few days before full is very similar to its brightness at the start of the eclipse. Practice focus, reading exposure from your camera’s histogram, and adjusting your tripod or star tracker in the dark. Check your photos on a computer to see how you’ve done with all the settings before you shoot the eclipse.

Turn off image stabilization. It’s unnecessary when shooting on a tripod, and you risk blurring your shots even if on a tripod. Just turn it off!

Double-check your focusing—it can be the hardest part to get right. Don’t use your camera’s autofocus, as it may have difficulty locking on to the Moon as it gets dimmer. Don’t trust your lens’s “infinity” mark, as that’s not always accurate.

Instead, switch your camera to use manual focus mode. Then use your viewfinder magnifier to enlarge the Moon as much as possible and then manually focus. Periodically check your camera focus as the night progresses. Temperature can affect your lens focus point so make sure it hasn’t drifted or been bumped.

Find the Moon’s Path

A phone app that shows the path of the Moon is a great help. Apps like Photographer’s Ephemeris, PhotoPills, PlanIt! for Photographers, or Stellarium can all show you where the path of the Moon will be at any time. I’ve used all these apps and they all have different advantages, so try a couple out before the eclipse. There are great videos online to help you learn these apps.

Use your app to determine how high the Moon will be for your location as the eclipse progresses. If you plan to shoot with a wide-angle lens, consider any interesting landmarks you can incorporate into your photograph. Perhaps there’s a tree, building, tower, silo, windmill, or lighthouse that would be interesting along with the Moon in your photo. And if you plan on shooting with a telephoto, you might want to avoid tall structures near the Moon’s path for your view!

Check the Weather

Living in the Pacific Northwest, I can attest to troubles with the weather! The entire region can be cloudy for days on end. But in many places, people will have the option of driving some distance to avoid clouds. Thick, heavy cloud cover will obstruct your view of the eclipse, and you’ll want to prevent it. Even high clouds or hazy air can cause problems. Don’t worry too much about scattered clouds; they can make an image more interesting.

Dress Appropriately

After checking for cloud cover, check the predicted temperature for your chosen location. Bring warm clothes! Even if you’re lucky enough to experience this eclipse from a location with a warm climate, you’ll want to bring something as the night’s temperatures drop. You want to have an enjoyable evening, and you’ll need to dress appropriately. Handwarmer packs can be great to have for shooting during cold nights, too.

Sitting on the Job

A lawn or camp chair can help you pass the hours. Experiencing a 5-hour eclipse while standing will be memorable—in a bad way. Consider setting your tripod up so you can sit and see your camera’s LCD comfortably. You might even want a sleeping bag to help keep you warm as you sit.

Warm Drinks

If it’s cold or cool where you’ll be, bring something warm to drink.

Sunglasses at Night

When the Moon is high in the sky at the start of an eclipse, it can be hard to see the Earth’s shadow starting to move across the lunar surface. A trick some experienced lunar eclipse viewers use is to wear sunglasses. Yes, wear your sunglasses at night! (Apologies to those now having a flashback to 1984 and mentally hearing Corey Hart singing “Sunglasses at Night”.)

Sunglasses can help reduce the Moon’s glare and make the encroaching shadow more easily visible. After a bit, it will be apparent where the Earth’s shadow is as it advances across the Moon and you can take the sunglasses off.

RAW or JPG?

If your camera has a “RAW” file format setting, use it. The RAW file format records all the image data from your camera sensor, allowing you to make more adjustments and create higher-quality images when you edit your photos. JPG files compress the image data in a way that’s not reversible when editing them. Photos taken as JPG may look OK, but they do not contain as much information and will give lesser quality than starting from a RAW file.

One thing a JPG loses is dynamic range, the ability to record the difference between bright and dark parts of the image. Perhaps the most challenging part of lunar eclipse photography is capturing the brightest and darkest parts of the Moon in the same image. Pictures taken as RAW will better record this difference.

If you’ve never shot with RAW before, are nervous about it, or don’t have software to edit RAW files, set your camera to shoot in RAW + JPG mode. That way, you can return it later and process the RAW files.

Lens Choice

Decide what type of eclipse photos you want. There are generally four types you can take:

- Wide-Angle – Gives a large sky view but with a small Moon.

- Telephoto – Gives a close-up view of the Moon.

- Multiple Exposures – Usually taken with a wide-angle lens showing the eclipse’s progression in a single image.

- Star Trails – taken with a wide-angle lens, showing the Moon and stars as streaks across the frame.

Wide-Angle Lens

Using a wide-angle is the simplest way to photograph the lunar eclipse. It gives a large sky view and lets you incorporate a foreground into your photo. Try to find a place that doesn’t have a lot of nearby bright lights in your field of view. They can create a glare that may interfere with your photos. But something like a distant cityscape can be a perfect companion to the Moon.

Use a 24 mm to 35 mm lens for a full-frame format camera or a 16 mm to 24 mm lens for APS-C. If you want to shoot a star trail photo, use the wider ranges just given. If you have a point-and-shoot or cell phone, set it to its widest setting. Even a standard lens could work here, depending on the framing of some photos, as it will appear like a wide-angle lens compared to a telephoto.

Even with a wide-angle, you’ll want to take exposures up to five seconds, so a solid tripod is needed. Use a remote trigger or your camera self-timer so you don’t create vibrations while taking photos.

![The multiple exposure image of the Moon above was created using a wide-angle lens. It rose during a partial eclipse in the early evening of 7 August 2017.

Credit: ESO/P. Horálek. [CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons]](https://photographthemoon.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/image-5.jpeg)

The multiple exposure image of the Moon above was created using a wide-angle lens. It rose during a partial eclipse in the early evening of 7 August 2017.

Credit: ESO/P. Horálek. [CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons]

Telephoto Lens

A telephoto lens will give the “classic” big Moon photo and record more detail on the Moon’s face. Do not use your camera’s “digital zoom” if it has that feature.

The classic “Big” Moon look. Filling the frame is not needed to get an excellent eclipse shot. Eclipse photos are more complicated unless the lens is on a tracking mount. The Moon moves fast when using long lenses! It will be out of the frame in a matter of minutes and you’ll spend most of your time trying to get the Moon back into your viewfinder at large magnifications. A crop sensor camera (Sony a6000) was used at 1260 mm for this image.

Photo Credit: ©2019 Kirk D. Keyes

To get some detail in the face of the Moon, you’ll want to use at least a 200 mm lens for a full-frame and 135 mm for a crop sensor. To fill the viewfinder of a full-frame camera, you’ll need a lens that’s about 2000 mm in focal length. An APS-C camera needs about 1200 mm, and a Micro 4/3 camera will need about 1000 mm.

Teleconverters are (sometimes) recommended

A teleconverter can increase the focal length of your lens. However, there are a couple of issues to be aware of when using teleconverters for eclipse photography. They decrease the lens’s effective f-stop, making exposure times slower. They can also create internal reflections that interfere with the image of the Moon.

Most importantly, unless it is a top-quality teleconverter, it will probably decrease the apparent sharpness of the picture. Considering these factors, I usually do not recommend using one. If desired, you can crop the image in post-processing to get a larger Moon.

You Don’t Need the Biggest Lens on the Block…

A 300 mm or 400 mm lens can look great. If you have a crop sensor, even a 200 mm will look incredible! They have enough magnification to see surface features on the Moon easily but also give enough space around the Moon that you don’t have to constantly re-aim your camera. Stars can even show up in the longer exposures needed for totality.

If you have a 3-way geared tripod head, this is a great time to use it. You can make fine adjustments to where the camera is pointed, making it easier to track the Moon.

Multiple Exposures

A series of photos taken with a wide-angle or telephoto lens show the eclipse’s progression in a single image. After the eclipse, combine the exposures into one image using Photoshop or another image-editing program.

Use your planning app to determine the moon’s path across the sky. If using a wide-angle lens, frame the image so the Moon starts on the right side of the frame. Plan on leaving the camera pointing in the same direction for the entire night.

Multiple Exposure Composites can be made by combining any image of the Moon in an image editing program like Photoshop. For this image, I combined four photos that I took at various stages of the eclipse and created a new image.

Photo Credit: ©2019 Kirk D. Keyes

With a wide-angle lens, you may want to focus the lens at the hyperfocal distance, so that your foreground subject will be in focus. Since you’ll be opening the f-stop as the eclipse progresses, calculate the hyperfocal distance using f/5.6 or even f/4. That way, you will not lose good foreground focus during mid-totality when the lens is open widest.

If using a telephoto, focus on the Moon directly.

Expose a Series

Make a series of exposures taking one photo every 1, 2, or 5 minutes. More images are always better than less as you can decide how many you want after the eclipse.

You also have the option to make a time-lapse if you shoot enough frames. Shooting one per minute for the duration of the eclipse would give 315 shots, which would make a time-lapse film that would last about 10 seconds.

Start taking photos a bit before the eclipse begins for the best effect. An intervalometer will help with this immensely! You may want to adjust your camera to track the Moon as it moves across the sky.

When it’s time to make your composite, keep your image natural-looking. Nothing breaks the feeling of a well-done image more than a poorly executed composite. Remember that it’s easy for people to spot a faked “supermoon,” especially when there is more than one in the shot!

Star Trails

A “star trail” photo of a lunar eclipse shows the Moon and stars streaking across the frame, like a traditional star trail photo. The motion of the Earth’s rotation will cause the Moon and stars to move, giving the image a sense of motion and time. This type of photo is an easy way to incorporate the landscape into the image.

To capture a star trail photo of the lunar eclipse, put the camera on a sturdy tripod with a wide-angle lens and aim the lens to capture the Moon’s path during the entire eclipse. Use the app you used to plan your shooting location to figure out the moon’s path across the sky. Usually, the Moon is placed near one corner of the frame to give it room to move. Remember that its path will be curved as it moves across the sky unless the camera is pointed due east or west.

A lunar eclipse captured in a “star trail” photo.

Photo Credit: “Winter Solstice Lunar Eclipse Startrails”, Robert Snache from Rama First Nation – Spirithands.net https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/legalcode

The most complicated part of this type of shot is allowing space in the frame for the Moon to move during the eclipse. The January 2019 total lunar eclipse will last about 5 ¼ hours. The Moon will move nearly 80° across the sky during that time. That’s just a bit more than the diagonal view of a 24mm lens on a full-frame or 16mm on a crop sensor camera. If you want the Moon to move horizontally across the frame, a 20mm will be needed for a full-frame and 14mm for a crop sensor. You can use this website to determine the angle of view for your camera/lens combination.

Maybe Just a Little

Remember that you don’t need to capture the entire eclipse duration for a star trail shot. See the example photo above. It looks like a partial eclipse and captures more of the Moon before totality than after it. Be creative with your location and the motion of the Moon for your photo.

You may want to focus the lens at the hyperfocal distance so that your foreground subject will be in focus. Since you’ll be opening the f-stop as the eclipse progresses, calculate the hyperfocal distance using f/5.6 or even f/4. Set the lens at the hyperfocal distance for your widest planned f-stop. That way you will not lose good foreground focus during mid-totality when the lens will be open widest.

Test Your Exposure

Before the eclipse begins, try a few test shots. Start with the camera at ISO 400 and the lens at f/8 or f/11. Set the shutter to the longest setting the camera can do, typically 30 seconds. Some intervalometers/remote releases can be programmed to allow exposures longer than 30 seconds—try 60 or even 120 seconds.

Don’t try to shoot the entire star trail shot with a digital camera with one exposure. You’ll run out of battery and the noise from your sensor will ruin the shot.

If the test images are overexposed, then stop the lens down half a stop or one stop. If the sky is too noisy, decrease the time the shutter is open or the ISO. Try a few variations to see what works best for your camera.

Once you’ve picked your starting exposure and have your camera lined up for the path you want the Moon to take, turn on your intervalometer and take photos. Remember to leave a few seconds between exposures for your camera to store the shot to the memory card. But you do want to take pictures one right after the other.

Follow the Darkness

The Moon’s brightness will decrease as totality approaches, and the lens f-stop will be periodically opened by a half or one-stop. This allows the Moon to streak across the frame without getting too dark to see in the image. You’ll probably end up exposing at f/5.6 during totality. Remember to stop the lens down again as the totality ends and the Moon returns to full. Check your histogram quickly in between shots to monitor your exposure.

If you don’t have a lot of time or don’t want to stand around too long after totality, try to use this technique for the hour of totality. The Moon and the stars will move a reasonable distance during that hour.

Combine the images using an image processing program like Photoshop to create the star trails. Many excellent videos online demonstrate this technique.

Traditionally, a film camera was used for these shots as the shutter could be held open for several hours. If you have an old film camera that’s itching to be used, this is a great use for it if it has a cable release and can take an hours-long photo without any battery dying.

Atmospheric Distortion and Magnification

Keep your shutter speed high as the Moon moves noticeably when magnification increases. In addition to the Moon moving, the air between you and the Moon moves and can cause considerable distortion when using longer lenses. Try to keep shutter speeds faster than one second. It will be challenging as the eclipse reaches totality, so be prepared to raise your ISO to 1600 or even 3200.

I shot some videos of the moon, which show the atmospheric distortion of the moon’s image. It was filmed at nearly 4300 ft of elevation, above more than 13% of the atmosphere compared to sea level. The Moon was a bit more than 50° above the horizon and it was tracked. Even though surface winds were calm that night, you can see just how much distortion there is from the air. Here’s the video on YouTube: Moon at 1260mm 2014 10 08

Video of the Moon that shows atmospheric distortion.

Credit: ©2019 Kirk D. Keyes

Time to Head Out!

The big night is finally here. You’ve probably read this guide several times to become familiar with what you want to do. So here we go!

Arrive Early!

This is always a great goal, but sometimes it isn’t easy to achieve. Leave for your shooting location early so you can have extra time to finalize your spot. Especially if you are using a tracker, it’s nice to have extra time to set it up and dial in the tracker alignment.

Camera Gear to Photograph the Total Lunar Eclipse

Like most photoshoots, you’ll want to bring the basics and a few extras:

- Camera

- Lens

- Sturdy Tripod

- Charged Battery plus spare

- Formatted Memory Cards.

- Remote release or intervalometer

- Dew shield and/or Lens Warmer (recommended)

- Star Tracker (optional)

Camera and Lenses

If you have two cameras, you might want to use one with a telephoto lens and the other with a wide-angle lens. The one with the wide-angle lens can either shoot a star trail or time-lapse of the Moon or the landscape during the eclipse. Try to put your gear to use, but remember you’ll need to focus on your camera with the telephoto lens way more than the others.

Lenses

Make your lens selection and go for it! Also, if you have any filters on your lens, remove them. When the Moon is so much brighter than the surrounding sky, it’s common to get either lens flare or an internal reflection between the lens and the filter. This will look like an upside-down image of the Moon. It’s most evident if the Moon is off-center of the frame and the reflection will show up on the mirror-imaged side of the frame from the Moon.

Sturdy Tripod

A sturdy tripod is required. Carbon fiber is the most popular material for tripod legs today, but don’t cross aluminum tripods off your list. They can still be a great choice, especially if you’re on a budget. Used tripods can often be found at excellent prices.

I have experience with and can recommend Benro and Leofoto tripods.

I love the Benro GD3WH 3-Way Geared Head. It allows for fine adjustments and is much faster to use precisely than a ball head. I currently have three.

Ensure your tripod head points high enough into the sky to aim at the Moon. I’ve had some 3-way heads that can’t point very high upwards—one of the adjustment handles hits the yoke of the tripod. My solution was to mount the camera pointing “backward” on the head and then tip the tripod head so the handle goes up and not down to where it hits the tripod. This was an easy solution, but maybe not one that would be anticipated with everyday tripod use.

A star tracker set to the lunar tracking speed will help keep you from having to readjust your tripod head.

Batteries

Bring extra batteries especially when it’s cold. Cold temps can suck the life from your batteries faster than an Energy Vampire. Like many Sony mirrorless cameras, some can be powered from a USB connector. Some cameras can use a “dummy battery” that replaces the actual battery in your camera and then plugs into an AC adaptor or a USB battery. Several types are available, check and see what will work with your camera.

If it’s cold, keep your spare batteries in an inside coat pocket to stay warm from your body heat. If the battery in your camera seems to be dying quickly, swap it out with a warm spare and put the “dead” one in your warm pocket. It may revive after your body has warmed it up.

At the least, have your batteries fully charged before heading out for the night.

Memory Cards

Bring a minimum of 2 memory cards, at least 32GB each. You should be able to store at least 500 RAW images with a 32GB card. Please have at least 2 in case of a problem with one of the cards (it gets lost, broken, malfunctioning…) I’ve had excellent results, that is no failures, with San Disk memory cards.

Remote Release / Intervalometer

While you can use your camera’s built-in self-timer to reduce camera shake, a remote release/intervalometer is more immediate. An intervalometer also allows cameras without a built-in intervalometer to make time-lapse sequences. The Pixel TW-238 Wireless Shutter Remote is a good choice as no cable hangs from your camera to the remote. Make sure you select the Pixel model with the correct camera adaptor. I have one for Sony cameras and I love it. It’s available for Nikon, Canon, and other cameras.

Do the Dew Shield

Use a dew shield or lens warmer, especially on colder nights. A dew shield is like a lens hood that extends several inches and wraps around the lens. It helps keep dew from landing on the front element of your lens. Make one in a pinch from some black plastic sheeting or card stock. You can tape it to your telephoto’s lens hood to secure it to your camera. You will not be able to use a dew shield with a wide-angle lens, but for a telephoto lens, it’s good insurance against losing photos due to moisture condensing on your lens.

A lens warmer can be used for wide-angle or even telephoto lenses. You can make one simply by taking some chemical hand warmers, like HotHands Hand warmers, putting a couple into a sock, and wrapping and tying the sock securely around the front of your lens.

Or you can buy an electrical lens warmer. They typically need 12V DC or USB power. They are easy to use, work well, and are convenient compared to chemical hand warmers. I can recommend the Move-Shoot-Move Lens Warmer. I have one, and it works well. You’ll need an external battery pack to power the USB lens warmer, look for one with more than 25,000 mAh, like this Anker Power Bank.

Star Tracker

While you don’t need a star tracker to photograph a lunar eclipse, it can make the job easier. The rotation of the Earth causes the Moon to move a distance equal to its width in just over 2 minutes. This motion is apparent when using telephoto lenses, especially when framing up close.

A star tracker is a mechanical device that lets your camera follow the motion of the stars. The tracker mounts on a standard tripod and sits between the tripod head and camera. A ball or 3-way head is usually mounted on the tracker to allow the camera to be pointed anywhere in the sky.

I’m a fan of the Sky Watcher Star Adventurer 2i – get the Pro Pack to get the wedge and counter weight.

Setting Up

Polar Alignment for Star Trackers

Trackers need to be aligned with the Earth’s axis of rotation to work. This is called “polar alignment” and there are several different ways to achieve it. Polar alignment can be difficult when taking the minute-long exposures needed for deep-sky astrophotography photos, but that level of accuracy is not required for lunar eclipse photographs. An alignment that’s good enough to keep the Moon where you want in the frame for 10 or even 15 minutes still keeps you from adjusting the framing every minute.

The Moon moves slightly slower than the stars, so some trackers have a setting for the Moon and stars.

I have a SkyWatcher Star Adventurer 2i, a great tracker choice. A tracker will cost around $300-500 USD to get it and the accessories needed to track the Moon. Other popular trackers are the Vixen Polarie, iOptron Skytracker, SkyWatcher Star Adventurer Mini, or the Move-Shoot-Move Tracker. These trackers vary in size and features, so compare them and see what will work best for you.

Now that you’re out in the field, there are just a few things to take care of. Since you’ve arrived early, use that extra time to get your tracker dialed in. It’ll pay off in the long run, as you’ll spend less time reframing your shots.

Switch to Manual Focus

Even though modern autofocus systems can do a great job focusing on a full Moon, I recommend you switch your camera to manual focus mode. Also, turn off image stabilization. Use a remote shutter release or self-timer to minimize camera blur. If you have a mirrorless camera, use “electronic front-curtain shutter”. For a DSLR, use mirror lock-up if your camera has it.

Focusing your Lens

Switch to Live View if your camera has it and turn up the magnification on the viewfinder. Then manually adjust the focus of your lens. Some people recommend not touching focus after that point, but I suggest you review your images occasionally to ensure you maintain good focus. It’s disappointing to spend the entire evening out taking photos only to find you lost focus 10 minutes into it.

Do not simply set your lens at the “infinity” or “∞” mark on the lens barrel. The accuracy of these marks is often questionable. You’ll get a much better focus using your camera’s LCD screen.

Focus Aid

A focus loupe can be helpful. It magnifies the rear camera screen so you can ensure your lens is at the proper focus point. I can recommend the Carson LumiLoupe. It is inexpensive, has a 10X magnification, and works great. Here’s a link for the Carson LumiLoupe.

Secure your Focus

If you’re using a zoom lens with the zoom adjusted by sliding the focus collar back and forth while the focus is made by rotating the same collar, you might want to set that lens to the focal length with the collar closest to the camera body. Over time, these collars can slip downwards, and you may lose focus.

Lunar Eclipse Exposure Settings

Exposure

Regardless of lens choice, the initial stages of the eclipse can be photographed using standard full moon settings – try using the “Looney 11 Rule”. It’s a variant of the “Sunny 16” rule for daylight exposure. For Looney 11, set the ISO to whatever you want, say 100. Then, adjust your lens to f/11, and finally, your shutter speed will be the same value you set the ISO to. So, if the ISO is at 100, set the shutter speed to 1/100 or 1/125 second, depending on your camera.

You probably don’t need or want to use f/11 when photographing the full Moon, so open the lens up a stop or two and select a shutter speed that maintains the Looney 11 rule relationship. ISO 100, f/5.6, and 1/400 second would be a great starting place.

Lunar Eclipse Exposure Guide| Lunar Eclipse Exposure Guidline | Table of Exposure Times | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ISO | Aperture | |||||

| f/2.8 | f/4 | f/5.6 | f/8 | f/11 | ||

| Full Moon | 100 | 1/4000 | 1/2000 | 1/1000 | 1/500 | 1/250 |

| Full Moon | 100 | 1/4000 | 1/2000 | 1/1000 | 1/500 | 1/250 |

| Gibbous | 100 | 1/2000 | 1/1000 | 1/500 | 1/250 | 1/125 |

| First/Last Quarter | 100 | 1/1000 | 1/500 | 1/250 | 1/125 | 1/60 |

| Crescent | 100 | 1/125 | 1/60 | 1/30 | 1/15 | 1/8 |

| Earthshine | 800 | 1/4 sec | 1/2 sec | 1 sec | 2 sec | 4 sec |

| Light Grey | ||||||

| Penumbral Eclipse | 100 | 1/2000 | 1/1000 | 1/500 | 1/250 | 1/125 |

| Partial Lunar Eclipse | ||||||

| Magnitude 0.00 | 100 | 1/2000 | 1/1000 | 1/500 | 1/250 | 1/125 |

| Magnitude 0.30 | 100 | 1/1000 | 1/500 | 1/250 | 1/125 | 1/60 |

| Magnitude 0.60 | 100 | 1/500 | 1/250 | 1/125 | 1/60 | 1/30 |

| Magnitude 0.80 | 100 | 1/250 | 1/125 | 1/60 | 1/30 | 1/15 |

| Magnitude 0.90 | 200 | 1/250 | 1/125 | 1/60 | 1/30 | 1/15 |

| Magnitude 0.95 | 400 | 1/250 | 1/125 | 1/60 | 1/30 | 1/15 |

| Total Lunar Eclipse/ Danjon Scale Value | ||||||

| L = 4 | 1600 | 1/30 | 1/15 | 1/8 | 1/4 | 1/2 |

| L = 3 | 3200 | 1/15 | 1/8 | 1/4 | 1/2 | 1 |

| L = 2 | 3200 | 1/4 | 1/2 | 1 | 2 | 4 |

| L = 1 | 6400 | 1/2 sec | 1 sec | 2 sec | 4 sec | 8 sec |

| L = 0 | 6400 | 2 sec | 4 sec | 8 sec | 15 sec | 30 sec |

Stop Down Your Lens

If possible, don’t use your lens’s widest aperture. Nearly all lenses are sharper when stopped down a bit from wide open. Stop your lens down one or even two stops from its widest aperture. So, if you have an f/4 lens, stop it down to f/5.6 or maybe even f/8.

During the transition from the penumbral to the umbral eclipse, it may be worthwhile to bracket exposures. The difference in brightness between the light and dark portions of the lunar surface will exceed the contrast range of many cameras. During this phase, try using a two-stop bracket (-2, 0, +2). You can combine these in post-processing to bring the contrast range down.

There will be a tradeoff between ISO, f/stop, and shutter speed, but be mindful of each while choosing your exposure settings. Remember to try to keep your shutter speeds as fast as possible to combat not only the rotation of the Earth but also atmospheric distortion.

Eclipse Exposure Calculator

An excellent site for planning eclipse photography exposures is by Xavier Jubier. He’s an engineer with a passion for both solar and lunar eclipses. He has a fantastic interactive exposure calculator online that’s worth checking out. Not only does it have an exposure calculator, but it can also show the size of the moon or sun for your camera and lens combination. Jubier’s exposure calculator can also tell you the slowest shutter speed to prevent any motion blur of the Moon with untracked photos. Make sure you check out his photo galleries for lots of fantastic eclipse photos.

If you’re going to be somewhere without internet service or like always to be prepared, Fred Espenak, aka Mr. Eclipse, has a handy exposure table you can print or download to take into the field. It covers all phases of the lunar eclipse and has settings for various combinations of ISO and f/stop. Here is his Lunar Eclipse Exposure Guide.

Histograms are Your Friend

Some photographers use the Sunny 16 exposure to start. Remember that your histogram is your friend regardless of how you start your exposure. It will probably have just one big peak at the beginning of the eclipse: the Moon. Keep it in the middle-right half of your histogram to avoid under or over-exposure. As the penumbra starts to move across the Moon, the histogram will flatten out somewhat, but keep any peaks you have on the middle-right half of your histogram plot. Don’t let them touch the far-right edge of the histogram.

Full to Penumbra to Umbra. Strike That, Reverse It!

During this eclipse, the Moon will pass through two parts of the Earth’s shadow. The Moon first enters the penumbra, which is the lighter shadow. Then enters the umbra, where totality occurs. It will reverse this order and reenter the penumbra, passing through it again until the eclipse ends. The umbra appears much darker compared to the penumbra. This transition is the hardest part of a total lunar eclipse to photograph. In addition, it’s impossible to predict exposures as the darkness of the umbra depends on the condition of the Earth’s atmosphere and how far the Moon passes into the Earth’s shadow.

The difference in brightness between the Moon’s surface as the umbra moves across will push the limits of your camera sensor latitude. The contrast range will decrease once more than the umbra covers half of the Moon. Give enough exposure to the darker part of the Moon to preserve its color. Try not to blow out the highlights of the Moon. Remember to bump up your ISO as the eclipse progresses to totality so your shutter speeds don’t get too slow. Try to keep them shorter than one second.

My God, It’s Full of Stars…

Another effect of a total eclipse is that more stars will be visible than on a regular moon-lit night. Way more stars! The sky’s brightness will change dramatically from start to midpoint and back to finish.

If you have a second camera, set it up for a time-lapse and point it at an interesting landscape feature. Remember to adjust the exposure/ISO as the eclipse proceeds. I’ve done this, and it’s interesting to see the brightness of the land change as the stars come out. The land will also reflect the color of the Moon during the eclipse. If possible, try incorporating the Winter Milky Way in the frame.

Example Lunar Eclipse Photos and Settings

For the total lunar eclipse on September 27th – 28th, 2015, I used a tracked telescope at 1260 mm and f/6.3. For the start of the eclipse, I used ISO 100 at 1/160 sec and dropped it to 3 seconds and ISO 200 for totality. The Moon traveled a similar depth into the Earth’s shadow during that eclipse as it will be for this eclipse.

At that exposure, the brightest part of the Moon was near overexposure while the darkest part was near black. I should have bumped up the ISO to get shorter exposures for this eclipse, as the Moon was low in the sky, and the atmosphere blurred the shots more than I wanted. Lesson learned: Use a faster ISO to keep the shutter speeds higher.

Initial Settings

The Moon just after the beginning of the eclipse on October 8th, 2014. Notice how the histogram shows a prominent peak on the right half. During this eclipse penumbral phase, you’ll want to keep that peak on the right side, but do not let it get too close to the edge. This photo was taken using a Sony a6000 APS-C camera connected to an 8” f/10 Meade LX-200 Classic with a 0.63 Focal Reducer. This combination produces a lens that is 1260 mm at f/6.3. ISO was 800 and the shutter speed was 1/2000 second. Photo Credit: ©2019 Kirk D. Keyes

For the October 8th, 2014 total lunar eclipse, with the same tracked telescope at 1260 mm and f/6.3, I started the night out with ISO 800 at 1/2000 second. (See the Lightroom screenshot above.) Notice the peak on the right half of the histogram. It’s not touching the right edge, but it is to the right and well placed to get a good exposure for the Moon.

Partial Phase Settings

When the umbra covered about 50% of the Moon, I had lowered the shutter speed to only 1/1600 seconds. (See the Lightroom screenshot below.) Notice the histogram in this image. As the Moon has darkened, the peak on the right half of the histogram has flattened out. I kept the brightest pixels towards the right side and again ensured they were not touching the right edge of the histogram.

I then slowly increased the exposure by decreasing the shutter speeds as the umbra continued across the lunar surface. All this time, the brighter part of the moon (still in the penumbra) was held at the same apparent brightness in the exposures. The part in the umbra was nearly black—it looked rather like a typical crescent moon, but the transition area was much softer than on a crescent.

The umbra covered the Moon about half during the eclipse on October 8th, 2014. This photo was taken using a Sony a6000 APS-C camera connected to an 8” f/10 Meade LX-200 Classic with a 0.63 Focal Reducer. This combination produces a lens that is 1260 mm at f/6.3. The ISO was 800, and the shutter speed was 1/1600 seconds.

Photo Credit: ©2019 Kirk D. Keyes

Notice how the prominent peak in the previous histogram example has now flattened out and stretches from the middle of the right side down to the left edge. During this umbral phase of the eclipse you’ll want to keep that flattened peak towards the right side again, but do not let it get too close to the edge.

Nearing Totality Settings

When the umbra covered 90% of the Moon, I was at ISO 800, f/6.3, and 1/10th second. Some color was starting to emerge in the dark part of the Moon while the part still in the penumbra was overexposed.

Totality Settings

When totality started, I used 1.6 seconds, still at f/6.3 and ISO 800. This gave a nice-looking shot with the brightest part of the Moon nearly overexposed and the darkest part showing a deep red color.

I continued to use settings around this exposure for the rest of the totality. In hindsight, they are a little dark and could have used bumping the ISO up to 1600.

Totality has just begun. This photo was taken using a Sony a6000 APS-C camera connected to an 8” f/10 Meade LX-200 Classic with a 0.63 Focal Reducer. This combination produces a lens that is 1260 mm at f/6.3. The ISO was 800, and the shutter speed was 1/1600 seconds.

Photo Credit: ©2019 Kirk D. Keyes

In the above photo, totality has just begun. At this point during the October 8th, 2014 eclipse, the umbra fully covers the Moon. The “1:30” point of the Moon is much brighter than the rest of the lunar surface.

Aim for Shorter Exposures

This exposure is at ISO 800, f/6.3, and 1.6 seconds. To get a sharper photograph, I should have raised the ISO to 1600 and cut the shutter speed.

Notice how the peak stretched across the histogram in the previous example has moved even more towards the left edge. Like the Moon itself, the histogram has even gained some color! As can be seen from the histogram, the brightest part of the Moon is still not overexposed but it is getting very close. The darkest part of the Moon is not entirely black, but it is also very close. As with the other eclipse phases, you’ll want to keep that flattened peak towards the right side again, but do not let it touch the edge.

Don’t Panic!

Lunar eclipses are relatively slow events. The Moon is significant, and the distance from Earth to the Moon is much bigger. (If a flat-earther tries to convince you otherwise, ask them for proof of their claims!)

Even though the Earth moves around the Sun at 66,600 mph (30 km/s) and the Moon orbits the Earth at 0.635 miles/sec (1.02 km/s), the Moon only moves about its diameter each hour. The umbra is about 900,000 miles (1.4 million km) in length. That’s about 3.7 times the distance from the Earth to the Moon. But the umbra is only about 5600 miles across (9000 km) at the distance to the Moon. That’s about 2.6 times the diameter of the Moon, which is 2,159 mi (3474 km).

It won’t be a mad rush, like a total solar eclipse. So, don’t panic! And if you do, know where your towel is.

Get out there and Have Fun!

Remember that it is rather challenging to get tack-sharp images of the Moon. Lunar eclipse photography is one of the more complex types of photography that most people attempt. The atmosphere’s distortion, along with all the motion of the Earth and the optical issues associated with telephoto lenses or telescopes, make this challenging!

Don’t be disappointed if your shots aren’t as crisp as you hoped – it’s part of the nature of shooting through the entire Earth’s atmosphere. Remember that nature is working against you!

There is undoubtedly a learning curve to lunar eclipse photography. Hopefully, this tutorial has helped you learn to stop worrying and love the lunar eclipse!

If anyone asks why you wear sunglasses while photographing the lunar eclipse, tell them, “Don’t be afraid of the guy in shades, oh no! I wear my sunglasses at night…” Then repeat the last line a few times and walk away. Sorry, I just had to work on some lyrics from that Corey Hart song.

Eclipse Datasheet

NASA has a single page datasheet with timing for this eclipse, which can be found here:

2025 Mar 14 chart: This Eclipse Predictions by Fred Espenak, NASA/GSFC

Suggestions:

If you find this guide helpful, please share and enjoy.

And if you find any info that needs clarification or correction, please email me at kirk@keyesphoto.com.

Bonus points go to anyone that can identify all the movie references in this tutorial.

kdk 3/07/25

1276 210417